Following our Happy Birthday wish to the 1951 Convention, we gave a very short introduction to some of the interesting bits of that Convention. Here, we discuss some of the elements in the Convention, with a look back at the Travaux Préparatoires. The travaux préparatoires provide a look at what each of the States parties negotiating the treaty thought about the wording of each of the Articles, and a discussion on the meaning or intention of many of the provisions.

Convention standards for juridical status, employment, welfare, and administrative measures such as freedom of movement

On the subject of welfare, the Convention has several articles, dealing, respectively, with rationing, housing, public education, public relief, and labour legislation and social security (articles 20 through 24). So does that mean that as soon as someone shows up, they are entitled to every benefit of one’s generous welfare society?

Not precisely. Interestingly, the Articles make a few distinctions: some articles require that you treat refugees the same way as you treat nationals, and others require that you treat refugees as well as possible and/or not worse than other aliens in the same circumstance. Some of the articles make a distinction between refugees and refugees lawfully staying in their territory. Let’s take some examples:

| Refugees | Refugees lawfully staying | |

| Accord “the same treatment as nationals” |

|

|

| Accord “the most favorable treatment accorded to nationals of a foreign country, in the same circumstances” |

|

|

| Treatment “as favourable as possible and, in any event, not less favourable than that accorded to aliens generally in the same circumstances: |

|

|

What do we mean by lawfully staying?

The distinction between refugees (generally) and refugees lawfully staying in the territory is one made throughout the 1951 Convention. According to the travaux préparatoires:

[T]he mention of ‘refugees’ without any qualifying phrase was intended to include all refugees, whether lawfully or unlawfully in the territory. (Art. 20)

The expression ‘lawfully within their territory’ throughout this Draft Convention would exclude a refugee who while lawfully admitted has overstayed the period for which he was admitted or was authorized to stay, or who has violated any other conditions attached to his admission or stay.’ (TP, Art. 15)

The discussion around “lawfully staying” draws a distinction between “lawfully staying”, “unlawfully staying”, and “lawfully in (but not resident of)”. It is related to the manner of entry, and the final phrase resulted at least partially from difficulties in translating French terms such as résidance habituelle and se trouvant régulièrement into English, because of differences in the meaning between résidance and the somewhat more permanent residence (domicile and sojourn were suggested as possible alternatives). The same can be inferred from Article 31 (“Refugees Unlawfully in the Country of Refuge”), which prohibits States from imposing penalties on those who enter or are in the territory “without authorization”. Interestingly, Article 31(2) discussions what restrictions of movement may be applicable “until their status in the country is regularized or they obtain admission into another country.” But there is no requirement for permanent asylum or a specific legal status of refugees.

The Travaux conclude with the following definition:

It results from the travaux préparatoirs that any refugee who, with the authorization of the authorities, is in the territory of a Contracting State otherwise than purely temporarily, is to be considered as ‘lawfully staying’ (‘résidant régulièrement’).

Hathaway makes the point that that “a refugee is lawfully staying (résident régulièrement) when his or her presence in a given state is ongoing in practical terms. This may be because he or she has been granted asylim consequent to formal recognition of refugee status. But refugees admitted to a so-called “temporary protection” system or other durable protection regime are also lawfully staying. So long as the refugee enjoys officially sanctioned, ongoing presence in a state party, he or she is lawfully staying in the host country; there is no requirement of a formal declaration of refugee status, grant of the right of permanent residence, or establishment of domicile.” The footnote to this paragraph notes, “This understanding is consistent with the basic structure of the Refugee Convention, which does not require states formally to adjudicate status or assign any particular immigration status to refugees, which does not establish a right to permanent ‘asylum,’ and which is content to encourage, rather than to require, access to naturalization.” (p. 730)

What’s the point? Rights in practice

Education

If we return to the table above, we see that some of the rights, such as rationing and public elementary education, are meant to be extended to any refugee (= anyone with a well-founded fear of persecution etc etc) on the same basis as nationals. There should be no distinction between refugees and nationals, and (according to Article 3) with no discrimination on the basis of race, religion, or country of origin. In practice, however, there are quite a lot of challenges in ensuring refugees’ access to primary education: some of the countries that have not signed the 1951 Convention may treat refugees as illegal migrants and restrict their access to schooling; educational opportunities may be limited and often vary accross camp and urban settings within a country; and refugees face frequent disruptions to their schooling. But issues about education for refugees is a whole other post.

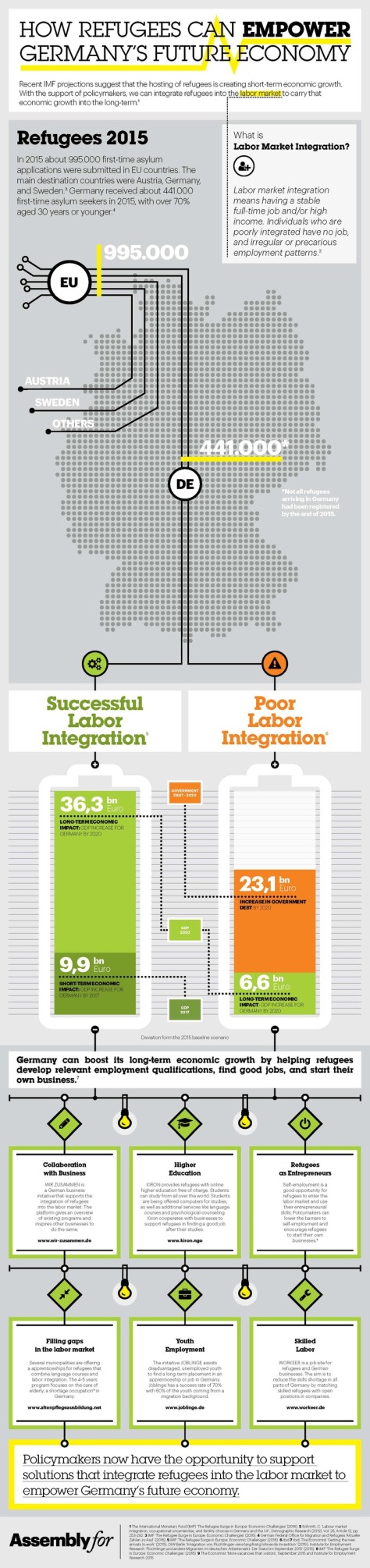

Right to wage-earning employment

Dr Paul Weis, in his commentary to the Travaux, characterized this Article as “one of the most important.” Refugees lawfully staying are to be accorded “the most favorable treatment accorded to nationals of a foreign country, in the same circumstances”.

The second paragraph does not mean that refugees must be granted national treatment. In many countries aliens require a work permit and in this case, it is required of refugees, too, unless they have been specifically exempted from it, but it

has to be accorded to them ex officio if they fulfil any of the conditions stipulated in paragraph 2. It does not exclude conditions attached to the admission of refugees or their stay. Measures for the protection of the national labour market are either measures imposed on aliens such as restrictions in time or space or concerning employment in certain occupations, or restrictions on the employment of aliens such as fixing a certain number or percentage of aliens in general or in certain occupations or enterprises, or the provision that aliens may only be employed if no nationals are available for the job in question. As the Article provides that refugees shall be ‘exempt from restrictions’ it would seem not to exclude the imposition of restrictions in the future. Only restrictions for the protection of the national labour market are excluded, not measures taken in the interest of national security such as the prohibition of employment of aliens in defence industries. The prohibition of the employment of aliens in the civil service or in certain categories of the civil service which exists in many countries, is also not excluded.

Right to self-employmet

On the other hand, we have the rights to housing, liberal professions and self-employment, which are limited to refugees lawfully staying in a territory and the treatment should be “as favourable as possible and, in any event, not less favourable than that accorded to aliens generally in the same circumstances.” So if a restriction on exercising a profession would apply to a foreigner generally, that restriction would also apply to refugees. And this can be a big hurdle, because quite a lot of states have restrictions on foreigners working, exercising a profession, and owning businesses.

A look at the Travaux indicates that there was quite a bit of divergence in terms of States’ approach

The amendment was motivated in part by the fact that foreigners arriving in the UK were required not to engage in selfemployment without permission for a certain time, after which they were free to engage in any profession they choose.

The Turkish representative said under Turkish law, only nationals could be self-employed, and Turkey would consequently have to reserve its position on that Article, no matter what its wording. He thought the most acceptable solution would be to accord to refugees the treatment given to foreigners generally.

The Belgian representative was also in favour of according to refugees the treatment given to foreigners generally.

The US representative felt that solution would confer no real benefits on refugees, and wondered whether it might not be possible to find a third solution, whereby refugees would be granted not the most favourable treatment, but a treatment more favourable than that given to foreigners generally.

So what happens in reality?

Despite the very explicit protections for the right to work in the Convention, and complemented by other international instruments such as Article 6 of the International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (which provides the “right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts” unfortunately, the IESCR only requires States to “take steps” towards that right), there is still a long way to go on refugee employment: a number of states have outright bans on employment, and access to employment in countries where it is legal often have significant de-facto barriers, like strict encampment policies, fees for permits, or administrative barriers such as document or bank account requirements that may be in practice impossible to fulfill.

Let’s look at the right to self-employment. This should be understood to also encompass the opening of businesses. The article refers to the right to self-employment, “as regards the right to engage on his own account in agriculture, industry, handicrafts and commerce and to establish commercial and industrial companies.” Self-employment “on his own account” was seen as a low-cost activity that states should simply “allow” to happen – but some scholars argue that this Article actually requires states to facilitate access to self-employment, i.e. access to arable land or remove administrative barriers.

But it’s not all bad news!

In South Africa, a precedent decision relied not only on Articles 17(1) and 18 of the Refugee Convention, but also an article of the South African Constitution that guarantees the right to human dignity, to hold that refugees and asylim-seekers have a right to open businesses to avoid starvation or destitution:

In Somali Association of South Africa, et al., v. Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment, and Tourism, Judge Navsa overturned the lower court’s ruling and held that, because refugees might be left destitute without the opportunity to open businesses, refugees have the right to open businesses in South Africa.

In doing so, the Court drew support from Articles 17(1) and (18) of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which clearly favor giving refugees the right to work and self-employment, but falls short of demanding that a State must allow refugees to work. The Court therefore grounded its holding in municipal law. Section 27(f) of South Africa’s Refugees Act of 1988 indicates that refugees are entitled to seek employment. Additionally, Section 10 of South Africa’s Constitution guarantees the right to human dignity.

The Court’s precedent in Watchenuka held that the constitutional right to human dignity required that refugees be given the right to seek employment. In Somali Association, the Court extended this logic to require that refugees be allowed to open new businesses: “[I]f… a refugee or asylum seeker is unable to obtain wage-earning employment and is on the brink of starvation, which brings with it humiliation and degradation, and that person can only sustain him or herself by engaging in trade, such a person ought to be able to rely on the constitutional right to dignity in order to advance a case for the granting of a license to trade…” As a result of these two decisions, refugees and asylum-seekers in South Africa now have the right to apply for and renew business permits and licenses. It is unlawful for the government to close permitted businesses or confiscate property.

But the judge did not stop with legal observations, further noting that “one is left with the uneasy feeling that the stance adopted by the authorities in relation to the licensing of … shops was in order to induce foreign nationals who were destitute to leave our shores.” The Court’s decision should go some length to ensure that “destitute” refugees can live in dignity in South Africa. (Full article here)