December 10 is International Human Rights Day, commemorating the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948. Although the UDHR is not legally binding in the sense that a treaty is, many of its principles have been reflected in other international treaties, and there is a growing sense that the unanimous adoption by the General Assembly represents a strong commitment by States, which could be perceived as a principle of customary international law.

There are a lot of interesting elements to the UDHR, but let’s for a moment focus on Article 14(1): “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.”

If Article 14 is the officially non-binding human right, the binding version is expressed in Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention: “1. No Contracting State shall expel or return (” refouler “) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” The concept of “expel or return” also extends to not turning back people seeking asylum at the borders. So here we have a codified, binding right to seek asylum from persecution in another country.

But what about the part of “enjoying” asylum? The word was probably not intended to reflect “enjoyment” in the sense of amusement parks, beach holidays, or eternal happiness. However the fact that “seek” and “enjoy” are listed separately implies that crossing the border is “seeking” asylum, and “enjoying” asylum is something different.

Some of “enjoying” asylum might be related to the standards of treatment as a refugee. The 1951 Refugee Convention states a number of rights and privileges to which refugees should have access – rights to things like employment, education, and documentation, some of which we discussed in a previous post – but many of these rights, at least as written in the Convention, indicate that refugees should have rights comparable to those of other foreigners, and only in some limited cases should refugees enjoy rights on equal footing to nationals. There is an interesting article by Alice Edwards, which looks at exactly this topic as applied to the right to employment and the right to family life. Edwards concludes that, “There is no doubt that the 1951 Convention retains its ‘central place in the international refugee protection regime’ [ …] Yet it is similarly clear that the 1951 Convention does not cover the many rights nor deal with the range of issues facing forcibly displaced persons today.” (read the whole article here) Some of the main thrust of Edwards’ article is whether international human rights law or instruments such as the ICCPR or IESCR might fill the gap where the 1951 Convention does not fully ensure a meaningful existence for refugees.

Abstract: “Increasingly hard-line and restrictive asylum policies and practices of many governments call into question the scope of protections offered by the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Has the focus on the 1951 Convention been to the detriment and subordination of other rights and standards of treatment owed to refugees and asylum-seekers under international human rights law? Which standard applies in the event that there is a clash or inconsistency between the two bodies of law? In analysing the interface between international refugee law and international human rights law, this article looks at the right to family life and the right to work. Through this examination, content and meaning is offered to the almost forgotten component of the right ‘to enjoy’ asylum in Article 14(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948.” (Edwards, Alice, Int J Refugee Law (2005)17 (2): 293-330. doi:10.1093/ijrl/eei011

So what is really happening?

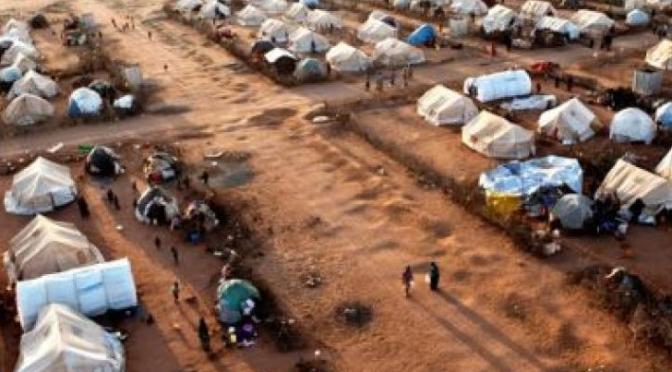

“For decades, the default response to refugee crises has been to set up camps or settlements and coerce refugees into them. Camps, it was argued, were best suited to meet the social, economic and political realities in which refugees are living. Yet a significant body of research has demonstrated the exact opposite, pointing to the fact that those refugees who have opted out of the camp system – even when that means forgoing any humanitarian assistance – have established an effective alternative approach to exile. They have managed to live in areas where they feel more secure, and have engaged in the local economy. Far from being passive victims, they have taken control of their lives, often without any external assistance. Until recently, however, there has been strong resistance to modifying policy to reflect this reality and harness the potential of refugees: the settlement model has suited the powerful interests of governments and UNHCR alike.” (full article)

We also have to take into consideration the length of time during which refugees are refugees. UNHCR frequently quotes the statistic of an average of 17 years (!) (although the source and veracity of that statistic has come to be questioned) in order to emphasize the point that refugees do not generally enjoy a brief stay before returning home; often, the displacement can last decades or generations. A US State Department report, quoting UNHCR, indicates that “UNHCR estimates that the average length of major protracted refugee situations is now 26 years. Twenty-three of the 32 protracted refugee situations at the end of 2015 have lasted for more than 20 years.”

Former UNHCR staffer, who headed the Za’atri refugee camp in Jordan, pointed out in a recent interview that,

“These are the cities of tomorrow, The average stay today in a camp is 17 years. That’s a generation. In the Middle East, we were building camps: storage facilities for people. But the refugees were building a city. I mean what’s the difference between someone in Philly and somebody in a refugee city? We have to get away from the concept that, because you have that status – migrant, refugee, martian, alien, whatever – you’re not allowed to be like everybody else.”

An interesting ODI study found that,

“Most displacement crises will persist for many years. A rapidly resolved crisis of any significant proportions is a rare exception. Data from 1978–2014 suggests that less than one in 40 refugee crises are resolved within three years, and that ‘protractedness’ is usually a matter of decades. More than 80% of refugee crises last for ten years or more; two in five last 20 years or more. The persistence of crises in countries with internal displacement is also notable. Countries experiencing conflict-related displacement have reported figures for IDPs over periods of 23 years on average. Understanding the likelihood of protractedness from the outset – and well before the five years that is the current UNHCR threshold for protracted refugee situations – should influence the shape and duration of national and international interventions.”

So where to now?

The conclusion is and should be that short-term approaches are not sufficient; that having asylum-seekers and refugees is a long-term commitment; that efforts towards self-reliance, livelihoods, and sustainability are important; and that it is not just enough to be able to seek asylum – refugees must be able to enjoy it, in some meaningful sense of the word. Efforts such as UNHCR’s Policy on Alternatives to Camps are a good start, but must be matched by hosting state commitments such as the fifteen countries who committed during the September 2016 summit to take concrete action to improve refugees’ ability to work lawfully by adopting policies that permit refugees to start their own businesses, expanding or enacting policies that allow refugees to live outside camps, making agricultural land available, and issuing the documents necessary to work lawfully.

Continue reading Happy human rights day! Now, what was that about ‘enjoying’ asylum?